In honour of April Fool’s Day, this week’s video looks at the classic cocktail the “Tom Collins”:

The name Tom, by the way, is a biblical name from a semitic root meaning “twin”, and the name Collins is a diminutive of Nicholas, which comes from Greek meaning “victory people”, the first element being Nike, the goddess of victory, who of course lends her name appropriately to the sportswear company. The inspiration for this video came from the story of the “Tom Collins” hoax, which presented the opportunity to cover a number of historical hoaxes, many of which I knew about because I’d been reading Justin Pollard’s entertaining book Secret Britain. The obvious timing for such a video was April Fool’s Day, so I could also include a bit about the history of that tradition as well. I should also draw special attention to the website of The Museum of Hoaxes, which provided much useful research, and is excellently well documented. (See the show notes page for all the sources used.) There’s also a timely footnote to this video in the recent rediscovery of that book Houdini hired H.P. Lovecraft (and co-writer C.M. Eddy) to write. You can read about the recovery of the manuscript of The Cancer of Superstition here.

The underlying theme behind this video, beyond the cocktail and the hoaxes and practical jokes themselves, is the way hoaxes tend to capture the spirit of the age they’re from. This is a bit similar to myth and urban legend, as I discussed in the video “The Story of Narrative”. When a hoax captures the public imagination, it sometimes does so because it is in tune with the zeitgeist, and reflects the preoccupations of the time. In this blog post I’ll have another look at some of the hoaxes mentioned in the video, as well as some others, in their historical context, to track this phenomenon.

But first a few more details about the origins of April Fool’s Day. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the earliest English use of the phrase April Fool is from 1629 in Edmund Lechmere’s A Disputation of the Church wherein the Old Religion is Maintained: “For my part, I was not willing at the sight of yours (which I espied by meere chaunce, and neuer sawe but once) to be made an Aprill foole, and therefore would not be so farre at your commaund.” So the tradition has been in England since at least that time. John Aubrey’s reference mentioned in the video is somewhat later in 1686. Though it isn’t a clear reference to April Fool’s Day itself, the earliest use of the French phrase poisson d’avril is apparently from 1508 in the poem “Le livre de la deablerie” by French composer Eloy d’Amerval: “maquereau infâme de maint homme et de mainte femme, poisson d'avril.”

Now as for Geoffrey Chaucer, he establishes the date for the story "The Nun's Priest's Tale" in a rather roundabout and perhaps intentionally foolish way: “whan that the month in which the world bigan, that highte March, whan God first maked man, was complet, and passed were also, sin March bigan, thritty dayes and two” (3187-90). (You can hear me reading out the full passage here, if you wish). Thirty two days since March began would be April 1st, but the following passage gives complex astrological indications that are more in keeping with a date in May: “Bifel that Chauntecleer, in al his pryde, his seven wyves walking by his syde, caste up his eyen to the brighte sonne, that in the signe of Taurus hadde y-ronne twenty degrees and oon, and somwhat more; and knew by kynde, and by noon other lore, that it was pryme, and crew with blisful stevene.” (3191-97). Now apparently, this information, if you account for the 12 days offset because of the change from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar, would yield a date of May 3rd, so many editors emend the text to “sin March was gon thritty dayes and two” making the date instead May 3rd there as well, a date Chaucer mentions quite often in other contexts as well and so is often referred to as his favourite date. What I wonder, though, is how much would this be off because of orbital precession in the 600-plus years since Chaucer’s time? At a rough guess I figure it would be out by over a week. Perhaps someone with more astronomical knowledge than I have can work this out. And in any case, all the manuscripts seem to agree on the reading “sin March bigan” so I’m inclined not to emend to “sin March was gon” and to try to make sense of the text as we have it. Since the tale contains a rooster and a chicken debating the philosophy of predestination and prophetic dreams, perhaps this dating is supposed to be inconsistent. In any case, take it as you will, but it may be of some small interest that Valentine’s Day also may owe its origin to a confused date in a Geoffrey Chaucer poem, The Parliament of Fowls, as I discussed in my video “Cuckold”. Or maybe Chaucer is just pranking us! (For more information, you can read The Museum’s detailed analysis of the Chaucer question here.)

There’s another connection here to Chaucer and my video “Cuckold”, in which I talk about the cuckoo bird. In the Wise Men of Gotham story we hear about the foolish attempt to fence in a cuckoo bird. Also, the cuckoo makes another appearance in the Scottish tradition, where April 1st was (and perhaps still is?) known as Hunt the Gowk day, gowk being the Scottish and northern English word for the bird, related to Old English geac. In the Scottish tradition the celebration continued with April 2nd being Tail day, when you stick a paper tail on people’s back, reminiscent of the French paper fish prank. So there does seem to be cluster of connections here, for what it’s worth.

In addition to the King John Gotham story, a number of historical events have been connected with April Fool’s Day over the years, such as the Dutch capture of Den Briel from Spanish forces on April 1, 1572, but none of these connections seem entirely convincing either. Now it’s possible that the tradition reaches back to some misrule festival which often takes place in the spring, such as the Roman festival of Hilaria, though there is little direct evidence for such links, but it’s been argued by Ronald Hutton (see show notes page) that as the misrule elements traditionally associated with Christmas faded, greater emphasis came to be placed on the spring equinox and April Fool’s Day. For more on the many and varied theories on the origins of April Fool tradition, see the Museum of Hoaxes very detailed page on the topic.

The Dreadnought hoax (about which you can read in full here) actually had a precursor. While studying at Cambridge, Horace de Vere Cole became friends with Adrian Stephen (Virginia Woolf’s brother), and the two started to get up to a number of minor pranks to entertain themselves. Their most elaborate was to pose as dignitaries from Zanzibar and enjoy an official reception from the mayor of Cambridge. It was years later that they decided to pull off a more elaborate version of the same prank, this time with some other confederates involved. The stunt seems to have been responsible for launching into public attention the loose collective of artists, writers, and other intellectuals known as the Bloomsbury group, which most famously included Virgina Woolf, and was in keeping with their pacifism and rejection of Victorian values.

There’s an interesting backstory to the Cock Lane Ghost affair. William Kent and Fanny Lynes were not legally able to be married as she was the sister of his now-deceased wife, and by law that was considered incest. They had thus moved from Norfolk to London to take advantage of the relative anonymity of the big city, where they could pose as a married couple. While staying at the house of Richard Parsons, Fanny would hear an otherworldly scratching noise, which she took to be her sister’s warning from beyond the grave of some great danger. This backstory and the mayhem of the Berners Street hoax (about which you can read more fully here), highlight the dramatic demographic changes going on in England in the 18th and 19th centuries, with the staggering shift in population from the countryside to the urban areas. From the 18th century onwards there was a dramatic overall rise in the English population, and following a trend already beginning in that century, at the start of the 19th century something like one-fifth of the population lived in cities, but by the end of the 19th century it was more than three-quarters, while the rural populations dropped.

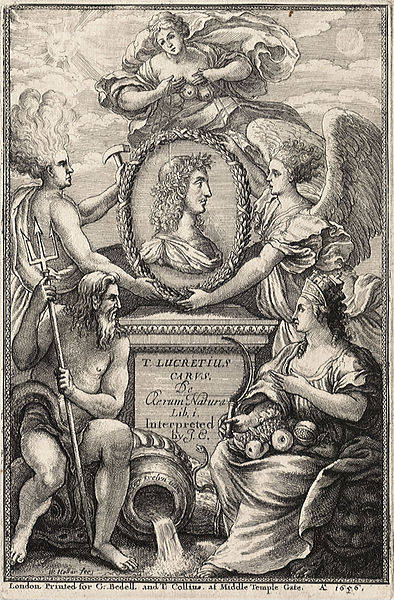

This alarming trend in demographics and the perceived threat of industrialisation is also one of the things that lies behind the celebration of nature and the countryside by the Romantic poets and artists. And it also explains their attraction to the medieval which they saw as a kind of golden age of a rural, pastoral world, with knights riding through the idyllic country on their chivalric quests. So they were ripe for the Ossian and Thomas Rowley medieval literary forgeries perpetrated by James Macpherson and Thomas Chatterton respectively.

Of course the science vs superstition tension also lies behind the Piltdown Man and Cottingly Fairies hoaxes. Photography was still relatively new by the beginning of the 20th century, so perhaps it’s not so surprising that people were fooled by photographs of cardboard cutout fairies. It’s interesting to note the impact that near ubiquitous camera phones have had on similar phenomena like UFOs and Bigfoot or Loch Ness Monster pictures. If one were to extrapolate from the frequency of such pictures before the camera phone, we should be flooded with evidence of the supernatural by now. Times change.

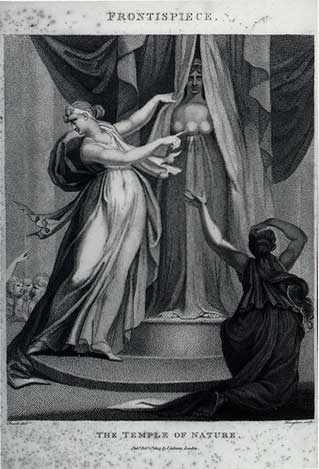

There are some other hoaxes that I didn’t have time to mention in the video, such as the 18th century rabbit babies of Mary Toft about which you can read the (disturbing) details here. What’s most notable about this hoax, which was accomplished by inserting rabbits (or parts of rabbits) into Mary Toft’s birth cavity after a miscarriage, is the number of highly respected physicians of the day who were fooled by it. This became the subject of scandal and satirical mockery, most notably by famous artist and pictorial satirist William Hogarth, who was critical of the gullibility of the so-called men of science in particular and of the general public more broadly, producing satirical cartoons about hoaxes of the day such as that of Mary Toft and Scratching Fanny. See for instance below, Hogarth's Cunicularii, or The Wise Men of Godliman in Consultation (1726) illustrating Mary Toft and her rabbit babies, and his Credulity, Superstition, and Fanaticism (1762) featuring references to both Mary Toft and Scratching Fanny, as well as other contemporary examples of secular and religious credulity.

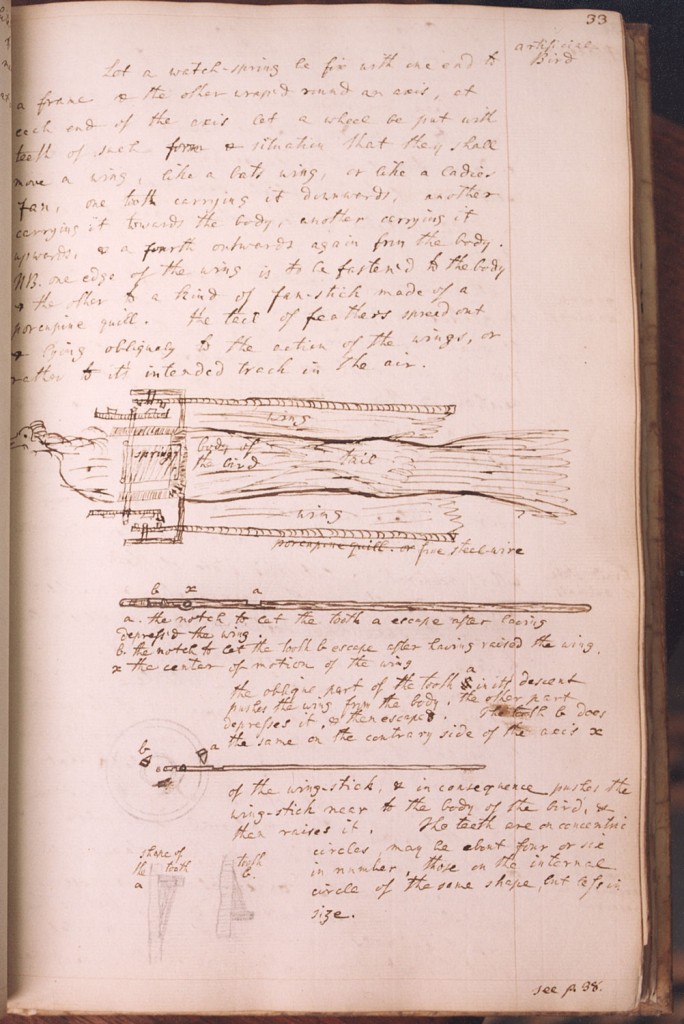

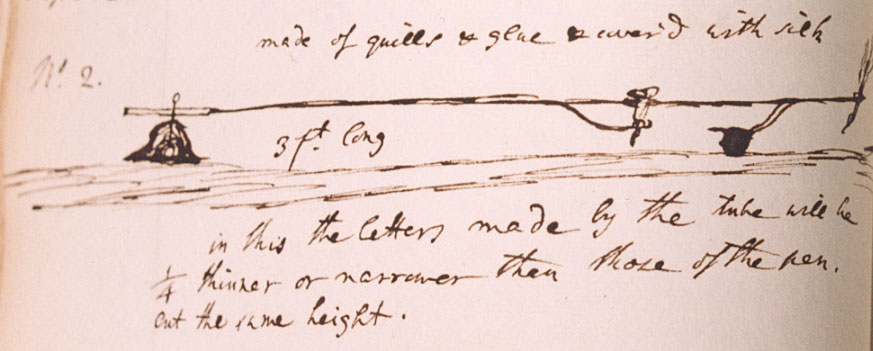

I mentioned a couple of hoaxes that Edgar Allan Poe was involved in, but in fact the Museum of Hoaxes documents a number of others here. As it turns out Poe was quite interested in hoaxes, not only perpetrating them but debunking them, as he attempted to do with the famous chess-playing Turk automaton, which appeared to be a mechanical device that could play and win against living opponents. Of course, as Poe suspected, there was an expert chess player hidden inside the machine (though not as he imagined in the body of the Turk itself, but in the mechanism beneath it) who was making the actual moves by means of a pantograph-like connection to the Turkish automaton above his head. The Mechanical Turk came with the Industrial Revolution, when machines were beginning to replace the labour of people. The idea of an actual thinking machine therefore played into the fears people might have of being replaced by machines.

The Mechanical Turk was invented by one Wolfgang von Kempelen who designed the speaking machine that Charles Wheatstone constructed and improved on that I mentioned in the “Erasmus Darwin” video. Interestingly, Poe used the name von Kempelen in another of his hoaxes. He published a newspaper article claiming that a German chemist named Baron von Kempelen had discovered an alchemical process to transform lead into gold, in the hopes of dissuading the inevitable gold rush that was about to ensue after reports of gold in California. One might imagine this was also a swipe at the creator of the Mechanical Turk as well.

One of my favourite hoaxes is the fictitious theologian Franz Bibfeldt. It began as a invented footnote in a student term paper, and eventually grew into an enormous in-joke. Academics and their senses of humour!

Speaking of academics, some scholars believe that Marco Polo’s Travels were a hoax, and that he never actually visited China, but instead based the book on second-hand accounts, due to omissions and inconsistencies in his record. There is much debate on this text, and ultimately it’s probably unprovable one way or the other. Of course the medieval period was full of faked holy relics — you can imagine how easy it would be to fake the finger bone of a saint or some such, and how lucrative it would be for the church donation box to have such relics. I mentioned perhaps the most amusing example of this in the Holy Prepuce, the supposed foreskin of Christ, in the Christmas video “The Twelve Days of Christmas”.

Of course sometimes writers can be taken in by hoaxes, as in the famous case of The Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown, who seems to have been taken in by a kind of crazy pseudo-history book about the supposed continued bloodline of Christ, co-written by Doctor Who scriptwriter Henry Lincoln, if that gives you any sense of the level of fantasy involved here, called The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, which was itself based on ‘evidence’ created by a surrealist hoax perpetrated by one Pierre Plantard and his confederates in the 1960’s. According to both books, the secret society known as the Priory of Sion, and the the Knights Templar preserved the Holy Grail, which was not the cup of Christ, but actually the secret bloodline of Christ and Mary Magdalen, which ran through the Merovingian royal family and right up to the present day, with secret messages and clues to its existence hidden in the art and architecture of the middle ages and renaissance. At least the convolutedness of Dan Brown’s plot lives up to the convolutedness of the trail of this hoax!

Apparently Plantard was trying to fabricate a connection between himself and the medieval French Merovingian royal family (and denounced the whole thing as fiction once the holy bloodline business had been introduced by Lincoln and his co-writers), and this is an interesting parallel with the hoax of the Vestiarium Scoticum, a supposedly old manuscript that established the provenance of the clan tartans in Scotland. This hoax was perpetrated by John and Charles Allen who were trying to claim they were the grandsons of Bonnie Prince Charlie. Unfortunately, though it was all made up, many of the tartan patterns are still considered as genuinely old and therefore official. As with the Da Vinci Code, which generated considerable tourist traffic to sites mentioned in the book, sometimes hoaxes get out of hand and take on a life of their own.

And it seems that the spirit of our current age is such that we want to believe in ancient or secret origins to things, and the easy availability of vast amounts of information appears (perhaps surprisingly) to make it easier to spread misinformation — so that we’re often taken in by conspiracy theories or other such hoaxes. If only our gullibility were just the result of too many Tom Collinses!