In my last post, I gave a brief potted history and explanation of the concept of linguistic relativity. Now I want to touch on some of the reaction to this new wave of research on linguistic relativity and talk a bit about my own take on it.

Through most of the 20th century there really wasn’t much solid evidence supporting the notion of linguistic relativity, and as I’ve said linguists were mainly focussed on looking for universals in language. So it is perhaps not surprising that in spite of the growing body of experimental evidence to support the idea, there is still considerable resistance. But in the recently burgeoning field of cognitive linguistics, linguistic relativity is starting to gain real traction again.

As Daniel Casasanto points out, most people who argue against the idea of linguistic relativity are objecting to the wrong thing.1 Most proponents of linguistic relativity don’t hold that language is the same thing as thought, just that it can influence thought. Casasanto proposes the simple (and quite elegant) mechanism of learning. Through repetition, language trains us into thinking in certain ways. Learn a new language and you are gradually trained into a new way of thinking. This is a convincing explanation that seems to fit much of the the data well. There is also evidence to suggest that we sometimes draw on language as a tool to aid thought. In some experiments, when your ability to use language is negated (by tying up your language faculties with other linguistic tasks like reciting a series of numbers), the linguistic relativistic effects lessen or disappear. Thus there may be more than one mechanism at work here. Clearly there is still much work that remains to be done to figure out the exact scope and parameters of this Whorfian effect.

It's interesting to note that many of the people who argue against linguistic relativity tend to focus only on strong linguistic determinism or other notions, such as the idea that language is thought, that few if any still argue for, and largely ignore the more recent work in this area. It's a bit of a straw man argument really. Or they'll focus solely on the false claims made in popular media on the topic. See for instance this very revealing debate on linguistic relativity from a few years ago. There certainly are a great deal of misleading and downright incorrect claims popularly made about linguistic relativity which is quite rightly deserving of criticism, but the popular media has a long history of misrepresenting the ideas of scientists and other academics, and none of this really reflective of the merits of the real argument itself. I do think that the weight of opinion will gradually shift as more research is done. I'm certainly convinced that at least some of what is claimed about linguistic relativity is true and valid, and well supported by the evidence that I’ve seen, but much of this research is still on the cutting edge of the fields of linguistics and cognitive science, so time will tell.

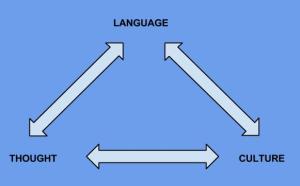

For my own part, it seems to me that we frequently ask the wrong questions when debating the validity of linguistic relativity. Does language influence thought, or does thought influence language? Well it’s likely both. And clearly there are external factors on both, what we might refer to as culture.2 It is perhaps best to think of a complex three-way relationship between language, thought, and culture, in which each influences the other two, which may lead to feedback loops with language, thought, and culture reinforcing each other back and forth. Furthermore, it is not at all surprising that often real-world evidence of Whorfian effects seem hazy, as one would expect multiple, often conflicting, linguistic influences on thought as well as multiple cultural influence. Rarely if ever would it be the case that an element of language is the only thing that influences some aspect of the way one thinks or behaves. But just because the Whorfian effect is frequently cancelled out or overruled doesn't mean it isn't operating beneath the surface. In highly controlled experimental situations, such as those Boroditsky creates, it is often possible to isolate a Whorfian effect, but it is such a complex system that practically speaking these effects may be hard to see clearly in the real world, though sometimes it seems to come out in startling ways. Again, even if the effects aren’t clearly visible, it doesn’t mean that the influences are not there. Human behaviour is complex and not easily reducible or predictable. See also my previous comments on interconnectivity -- it's the complex nature of the connections that's really interesting here.

I'm not myself concerned with isolating these influences or devising some kind of predictive theory about behaviour, though those lines of research are certainly important themselves. Since I come more from the humanities side of things rather than the sciences or social sciences, I'm more concerned with interpreting rather than predicting, so my main interest is seeing what linguistic relativity can tell us about the complex interrelationship between language, thought, and culture over time through the course of history. And as I've said, I see all these elements influencing each other. The (admittedly imperfect analogy) I like to think of is that even though the gravitational effect of a pebble on the earth is tiny compared to the effect of the earth on the pebble,that doesn't mean that it isn't there, and if enough pebbles start pulling in the same direction, metaphorically speaking, the effects can add up. Of course the tendencies of individuals may in many cases be far more variable than any Whorfian effect. The Whorfian effects might be the tipping point in an otherwise evenly balanced situation, or might only be noticeable in isolation or in the aggregate; but if they line up with other cultural influences the outcome might be profound, with the kind of feedback loop effect I alluded to earlier.

In any case, I've waffled on about this topic no doubt to the point of boring any casual reader into giving up on this post several paragraghs ago, so I'll stop now, though it's likely that the topic will come up again in future posts.

1 See Casasanto's excellent and wonderfully titled article "Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Whorf? Crosslinguistic Differences in Temporal Language and Thought". [back]

2 See Dan Everett’s fascinating work on the cultural constraints on language. Based on his research on the fascinatingly different language Piraha, Everett rejects the notion of universal grammar and concludes that language is constrained by culture and is in fact a cultural tool, an invention by human beings, not an innate instinct. See also Everett's more popularly targeted book Language: The Cultural Tool. I'll be writing more about these topics in the future, particularly as they relate to time in language and thought. [back]