As promised a couple of posts back, here is the related post on interconnectivity, or rather the first of what will probably be two posts on the topic. I was writing then about interdisciplinarity, essentially how different disciplines and subjects intersect and are interconnected. The underlying principle of this is the interconnectedness in everything in the highly complex phenomenon of our world. This post will be a demonstration of and exploration of the kinds of interconnections possible. In the next post I'll discuss some of the broader implications of interconnectivity.

The great fictional detective Sherlock Holmes is famous for his amazing powers of deduction. Using keen observation and deductive reasoning he is able to observe clues and work out the causes that lie behind any circumstance, a skill he frequently uses to solve crimes. He is able to see, in a way that other characters who inhabit Conan Doyle’s stories were not, the way seemingly unconnected facts can relate to one another. Other characters, such as his friend and companion Doctor Watson, are amazed and baffled until Holmes explains the deductive steps that led to his conclusions. Only then does the greater web of clues create a more complete and holistic meaning for both characters in the story and for the readers as well. Presented only with the starting point and the final conclusion, the chain of deductions seems remarkable indeed.1

This blog post is something of a literary/cultural/historical detective story that begins and ends with Sherlock Holmes. Or rather, it begins with another ‘detective’, Sir Gawain, one of King Arthur’s Knights of the Round Table, and the perhaps surprising suggestion that there is a connection between Sherlock Holmes and Sir Gawain. They are both detectives who have to follow a trail to solve a mystery, and they are connected by fascinating literary/historical trail.

A number of years ago, I was teaching a course aimed at first-year university students which focused on literature in the context of the arts and humanities. (It was intended for students who were not English majors.) I decided to take the approach of trying to demonstrate the cultural network that underlies all of western literature, that nothing existed in a vacuum, and that all of history, art, culture, philosophy, and science are inextricably linked. In order to understand the literary texts in the course, we had to examine the world that produced them in all its interconnected complexity. As it turns out, two of the works I decided to include in this course were the 14th century Arthurian romance Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and the Sherlock Holmes short story “A Scandal in Bohemia”.

Here follows a summary of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, for those who are unfamiliar with the story: In the early days of King Arthur’s court, at around the time of Christmas and New Year’s, all the nobles at court were feasting and celebrating, as befits that time of year. At one such feast, surprising everyone, a strangely green intruder burst into the hall riding a strangely green horse. Both horse and man are completely green, and the man carries with him two things, an axe and a holly bob. Holly had the same symbolic connection to Christmas then as it does now — mercy, rebirth, salvation. The axe, both a weapon of battle and the instrument of the executioner’s justice, had a particular lace wrapped about the handle. The strange green intruder proposed a game to the court, an exchange of blows. Gawain accepted the challenge on behalf of his king and court, and struck the head from the Green Knight using the axe. What was even more surprising was that the Green Knight picked up his head, reminded Gawain of his promise to accept a return blow one year later, and then rode out of the hall with his head carried under his arm.

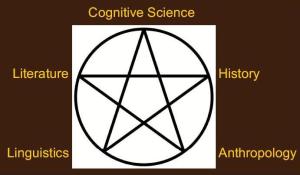

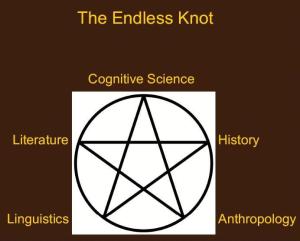

Thus begins Sir Gawain’s detective story. He must gumshoe his way around the countryside trying to track down the Green Chapel where he is to keep his bargain to the Green Knight, and along the way come to grips with the mysterious events that have precipitated this adventure. Unlike Sherlock Holmes, Sir Gawain is not an exemplary detective, and he fails to pick up on all the clues presented to him. Surprising, considering that his personal symbol, which he wears emblazoned upon his shield is the Sign of Solomon, a pentangle or five-pointed star also referred to in the poem as the Endless Knot, from which this blog takes its name and logo.2 It is so named because of its interconnectedness. One can draw a pentangle without lifting the pen from the page, and each point is connected to two other points of the star. It is indeed an interconnected, endless knot. For Gawain, this symbol represents the interconnected nature of his code of honour as a Knight of the Round Table. Furthermore, its connection to Solomon, a symbol of judgement from the Old Testament, represents his commitment to justice. (Incidentally, on the inside of his shield Gawain has the image of the Virgin Mary, a symbol of mercy, and thus the shield graphically represents the same set of oppositions that the axe and the holly symbolized, justice and mercy.) But although Gawain’s personal symbol is one of interconnectedness, he doesn’t himself grasp the interconnectedness of the events which befall him.

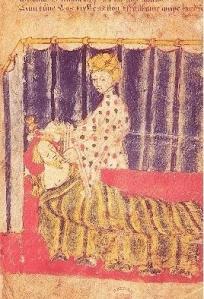

Sir Gawain heads out on a quest to find the Green Knight, and a few days before his appointment at the Green Chapel, Sir Gawain comes upon an unexpected castle in the wilderness where he may celebrate Christmas, quite possibly the last one of his life. The castle is circled by a palisade and moat two miles away, with the grounds within this palisade belonging to the castle. He is warmly welcomed there — perhaps a little too warmly. His host, Lord Bertilak, suggests another game of exchange, this time between daily winnings. The host will go out on a hunt each day and exchange what he manages to catch with whatever Gawain wins staying home in the castle each day. Unsurprisingly the host manages to hunt down various animals, namely a deer, a boar, and a fox. Gawain’s daily winnings are somewhat more unusual. Each day his host’s wife, Lady Bertilak, who is the femme fatale of this detective story, visits Gawain in his bedchamber and attempts to seduce him, having heard of his fame as chivalrous knight of King Arthur’s court who is as successful at wooing women as he is fighting on the battlefield. Gawain, of course is in something of a quandary, having agreed to the game of exchange. Anything he ‘wins’ must be passed along to his host at the end of the day. Each day Gawain manages to squirm his way out of having an affair with Lady Bertilak, accepting only kisses from her, which he dutifully passes on to the host each evening.3

However, on the third day he finally breaks his word. Lady Bertilak offers him her lace girdle, and if this seems a sexually charged gift, it is. She offers him an undergarment in much the same way that a groupie would throw her underwear at a rockstar today, given Gawain’s rockstar fame as one of the Knights of the Round Table. Only it’s not just any underwear, it’s magic underwear! Lady Bertilak tells him that if he wears this lace, he will be impervious to any harm. Now Gawain has a way of surviving the fateful encounter with the Green Knight, but only if he breaks his word and doesn’t give up his winnings to his host that evening, and this is exactly what he does. Perhaps had Gawain not been so concerned for his life, not only would he have not broken his word, he might also have picked up on the clues that he was being set up. He had all the information he needed to deduce the meaning of this mystery, but unlike Sherlock Holmes, he fails to see the connections. He had in fact already before seen the lace the wife gave to him, around the handle of the axe the Green Knight was carrying. And upon arriving at the castle, he was told the Green Chapel was not two miles away, and therefore within the walls surrounding the castle grounds. But he doesn’t connect these and other clues to come to the conclusion that all these events are interconnected, and that the outcome of the exchange of winnings game is tied to the outcome of the exchange of blows game. As it turns out, the Green Knight, who is also his host at the castle in a magical green disguise, judges his error to be a minor one, and only scratches Gawain with the axe. Gawain, however, learns his lesson. He chose poorly, picking the axe of judgement rather than the holly bough of mercy, and didn’t fully live up to his code of honour as a knight.

Thus ends this detective story, one part of the larger cycle of Arthurian legends and romances. The Arthurian stories encapsulate the medieval mindset perhaps better than any other works of literature, with conflicts between religious belief, martial conquest, devotion to women in the courtly love tradition, and personal codes of honour. Of course, to a large extent, this was an imaginary world. Already, in the middle ages, writers were looking back on a golden age of chivalry which never really existed, at least not in the way it was portrayed in courtly romances like Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. But it was a powerful and resonant set of images and ideas, one which continued to be drawn upon by writers in successive ages.

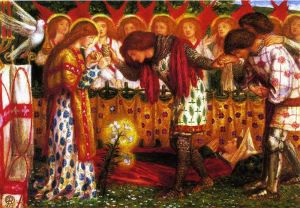

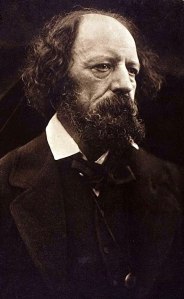

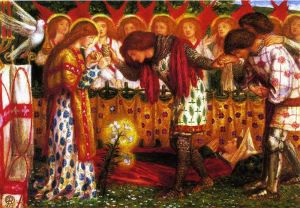

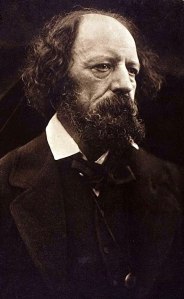

One such later age which drew heavily upon the medieval was the Victorian period. Many Victorian writers, artists, and thinkers, such as Alfred, Lord Tennyson, William Morris, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Thomas Carlyle, and John Ruskin, looked to the medieval for imagery, ideas, and inspiration. Again, it was something of a romanticisation of a medieval golden age that never really existed in quite that way, but it was nevertheless a major part of the Victorian aesthetic. Tennyson is often thought of as the quintessential Victorian poet, reflecting all the many cluttered aspects of Victorianism, including Victorian medievalism. One of his most famous poems is Idyls of the King, a poetic retelling of the Arthurian story (though not the story of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight). Tennyson’s poem is an attempt at writing the great British epic, with the Arthurian story reflecting on the British monarchy. Indeed, Tennyson frequently reflects the concerns of his day – everything from the conflict between faith and science, which was brought into sharp focus by the new evolutionary theories of the day, to the appalling social conditions that resulted from industrialisation, sharply contrasted by the pastoral world of Arthurian legend. Indeed, Tennyson was officially adopted as the poetic voice of the age when he was named Poet Laureate.

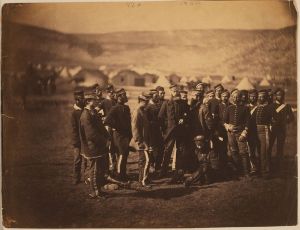

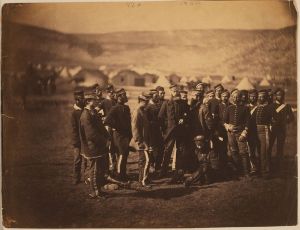

One particular national issue which Tennyson wrote about after being named Poet Laureate was in his other most famous poem, “The Charge of the Light Brigade”.4 This poem tells the story of a disastrous attack in the Crimean War. A misunderstood order caused the Light Brigade to charge, and they were all slaughtered. Tennyson seems to be celebrating the heroism of doing one’s duty and courage in the face of defeat, qualities at the heart of the Victorian self image. It was at the order of the commander of the British forces, Lord Raglan, that this disastrous attack was made.

Speaking of Lord Raglan, or more properly FitzRoy Somerset, 1st Baron Raglan, his great-grand-son FitzRoy Somerset, 4th Baron Raglan, also commonly known as Lord Raglan, was most famous for his scholarly work on the hero figure, and wrote about a variety of legendary heroes, including King Arthur. Raglan’s approach is to analyse the hero myth pattern that underlies such stories, such as Gawain’s journey in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

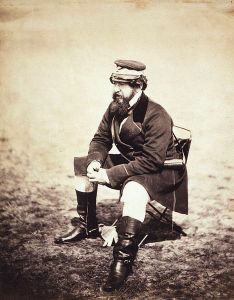

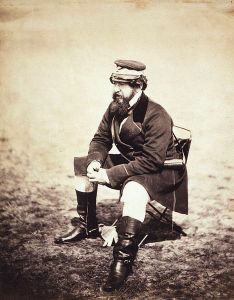

But getting back to Raglan senior and the Crimean War, the general poor organisation and appalling conditions endured by the troops were written about by the world’s first war correspondent William Howard Russell. Russell’s dispatches, published in The Times, created much controversy and uproar back home, and as a result Raglan ordered his officers not to talk to Russell. But not before Russell’s stories brought Florence Nightingale, along with a team of nurses she trained, to Crimea to see to those poor conditions being suffered by the troops.

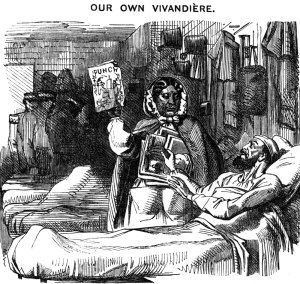

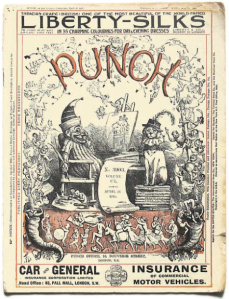

Florence Nightingale became famous for her pioneering efforts in wartime nursing. But she wasn’t the only notable nurse involved with the Crimean War. Rather less well known than Nightingale is the Jamaican nurse Mary Seacole.5 Seacole travelled from Jamaica to England to volunteer as a nurse for the Crimean War soldiers, bringing her knowledge of tropical medicine (with herbal and folk remedies). She was rebuffed by the authorities (at least in part due to racial prejudice, since she was of mixed race). Seacole managed to raise the money independently, and she went anyway, setting up her own hotel for the care of wounded soldiers, which she financed by selling food and drink to the soldiers. She is notable for sometimes treating soldiers on the battlefield under fire. Though the soldiers and military commanders seemed to appreciate her efforts, Nightingale herself was dismissive of Seacole, and after the war ended she returned to England destitute. Her plight was brought to public attention in part through Punch magazine, the famous satirical Victorian periodical.6

There was something of an explosion in periodicals in the 19th century, driven in part by cheaper paper and advances in printing technology. This allowed for low-cost, mass-circulation periodicals, which coupled with increased literacy rates led to a market for popular literature, literature for the masses. Indeed there was a mini-explosion of printed media in the 19th century, what with the periodicals, the proliferation of broadsheet newspapers, and the penny dreadfuls, which led to a kind of information overload similar in effect to the digital media explosion of our own time. This in turn led to more and more affective and even sensational content in order to grab the attention of the readers.

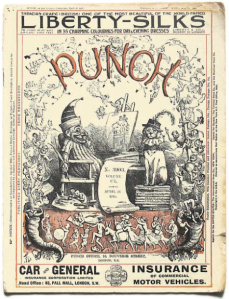

Richard “Dickie” Doyle was a famous Victorian illustrator who drew the Punch magazine’s first cover, and therefore designed the Punch masthead used for over a century. Doyle contributed various illustrations for the magazine,7 as well as illustrations for a variety of famous Victorian authors such as Dickens, Ruskin, Thackeray, and Leigh Hunt, often signing his initials RD with a dickie bird standing on top (see the bottom left corner of the image above). Richard Doyle’s nephew came to prominence, feeding the public desire for sensational content such as stories about crime and other lurid topics, in the pages of another famous Victorian periodical, The Strand Magazine, where Sir Arthur Conan Doyle published his stories about the detective Sherlock Holmes.

So here the trail ends, from one “detective” to another. In my final, half-improvised lecture to my students, I outlined this connection, which touched on several of the texts and historical contexts we had examined in the course. The point was (and is) that all these things are connected one way or another and to study any one of them inevitably leads to an unending trail of connections. Stay tuned for Interconnectivity part 2, wherein I discuss some of the theoretical background to interconnectedness, and explain why I’m so concerned with this...8

1 Here's an excerpt from "A Scandal in Bohemia" which demonstrates this:

"Wedlock suits you," he remarked. "I think, Watson, that you have put on seven and a half pounds since I saw you."

"Seven!" I answered.

"Indeed, I should have thought a little more. Just a trifle more, I fancy, Watson. And in practice again, I observe. You did not tell me that you intended to go into harness."

"Then, how do you know?"

"I see it, I deduce it. How do I know that you have been getting yourself very wet lately, and that you have a most clumsy and careless servant girl?"

"My dear Holmes," said I, "this is too much. You would certainly have been burned, had you lived a few centuries ago. It is true that I had a country walk on Thursday and came home in a dreadful mess, but as I have changed my clothes I can't imagine how you deduce it. As to Mary Jane, she is incorrigible, and my wife has given her notice, but there, again, I fail to see how you work it out."

He chuckled to himself and rubbed his long, nervous hands together.

"It is simplicity itself," said he; "my eyes tell me that on the inside of your left shoe, just where the firelight strikes it, the leather is scored by six almost parallel cuts. Obviously they have been caused by someone who has very carelessly scraped round the edges of the sole in order to remove crusted mud from it. Hence, you see, my double deduction that you had been out in vile weather, and that you had a particularly malignant bootslitting specimen of the London slavey. As to your practice, if a gentleman walks into my rooms smelling of iodoform, with a black mark of nitrate of silver upon his right forefinger, and a bulge on the right side of his top-hat to show where he has secreted his stethoscope, I must be dull, indeed, if I do not pronounce him to be an active member of the medical profession."

I could not help laughing at the ease with which he explained his process of deduction. "When I hear you give your reasons," I remarked, "the thing always appears to me to be so ridiculously simple that I could easily do it myself, though at each successive instance of your reasoning I am baffled until you explain your process. And yet I believe that my eyes are as good as yours."

"Quite so," he answered, lighting a cigarette, and throwing himself down into an armchair. "You see, but you do not observe. The distinction is clear. For example, you have frequently seen the steps which lead up from the hall to this room."

"Frequently."

"How often?"

"Well, some hundreds of times."

"Then how many are there?"

"How many? I don't know."

"Quite so! You have not observed. And yet you have seen. That is just my point. Now, I know that there are seventeen steps, because I have both seen and observed."

[back]

2 The blog URL uses the phrase "endless round", since The Endless Knot was already taken. The phrase "endless round" was used in the poem Pearl, in the same manuscript as Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and written by the same poet. It describes the image of the pearl, a symbol of perfection, and connected, I believe, with Gawain's pentangle. [back]

3 It's really quite a sexually charged poem, with kinky bondage sex-talk between the host's wife and Sir Gawain, and the implication of potential homosexual sexual favours between Gawain and his host. Medieval literature is by no means prudish and boring! [back]

4 If you've never heard this before, have a listen to this wax cylinder recording of Tennyson himself reading "The Charge of the Light Brigade". Amazing! [back]

5 You can read her own autobiography here. [back]

6 The poem published in Punch magazine is entitled "A Stir for Seacole". [back]

7 Though not as far as I can tell the one of Seacole. [back]

8 I hereby dedicate this blog post to Stevyn Colgan. If you want to read more interconnected detective stories, click here to read the first two chapters of his new book Constable Colgan's Connectoscope, and click here to sponsor the book and make sure it gets published. [back]