Happy holidays! This year’s Christmas video is all about the tradition of the Christmas stocking and the treats you get in it:

The main theme here, using the sugar coating metaphor, is to uncover the true and often unsavoury stories behind some Christmas traditions. First of all there’s St Nicholas, a rather stern figure originally, at times associated as much with punishment as reward, like the switch left in the shoe (or stocking) for punishing bad children — he knows when you’ve been bad or good, so be good for goodness sake! The punishment element of it all is further emphasized through the etymological connection between stocking and the stocks. There’s also the grisly story of the butchered and pickled young boys that Nicholas brought back to life. Not surprising perhaps that this one doesn’t make it into the modern Santa Claus mythos. And so much of the original Nicholas story is quite at home with the commercialization of Christmas that so many complain about today, as he’s the patron saint of merchants and pawnbrokers. And of course the merchant syndicate of Bari stealing the bones of St Nick to set up the first Santa’s grotto! One extra interesting detail about that story. Apparently as they tried to sail away with the spoils a storm blew up keeping them from departing, until it was found to have been caused by one unscrupulous, or should I say even more unscrupulous, member of the party who had secretly stashed some of the relics for himself. Once all of Nicholas’s bones had been gathered together, the ship was able to sail home. I guess it was another of Nicholas’s nautical miracles.

Of course another often overlooked element of the St Nicholas tradition is that he wasn’t a northern European, in spite of his connection to snow and reindeer. In fact he was from what is today Turkey. This is important to keep in mind in light of the recent furore over a black mall Santa, and the racist claims that Santa is white. Unfortunately there is a running racist subtext to much of this story, what with the Zwarte Piet tradition as well. Speaking of which, there’s one other explanation given of the Sinterclaas / Zwarte Piet tradition, that it represents a holdover from old Germanic myths of the god Odin (one of the other sources of the Santa figure that I discussed in my “Yule” video a couple of years ago) with his two servants, the black ravens Hugin and Munin, but the connection seems a bit of historical stretch.

Lest all this grim analysis give you the holiday blues, let me make up for it by giving you a few more entertaining tidbits that didn’t make it into the final video. One extra story about Pintard: I said he celebrated St Nicholas Day with his family. Apparently one year he made a life-size model of the saint on wheels and brought him out in front of his children on a pulley system. As Mark Forsyth reports in his excellent book A Christmas Cornucopia, his son “immediately screamed out that it was his dear departed little brother.” Poor child! When Irving took up the St Nick story, he actually published his history of New York under the suitably Dutch-sounding pseudonym Diedrich Knickerbocker, and as I said, the book became a huge success. So much so that knickerbocker became a nickname for New Yorkers, and the nickname, if you’ll excuse the pun, for their basketball team, the New York Knicks. This is also the source of the word knickerbocker trousers (as in, the type Dutch people typically wore), and the British term knickers referring to ladies’ underwear. So this joke really had legs!

Along with Moore’s famous poem “Twas the Night Before Christmas”, we also have another 19th century New Yorker, German-born Thomas Nast, to thank for our modern vision of Santa Claus. I’ve mentioned this famous caricaturist before in the “Cocktail” and “Ambition” videos. It was Nast’s depiction of St Nick that really cemented the figure in the minds of his growing army of followers and enthusiasts.

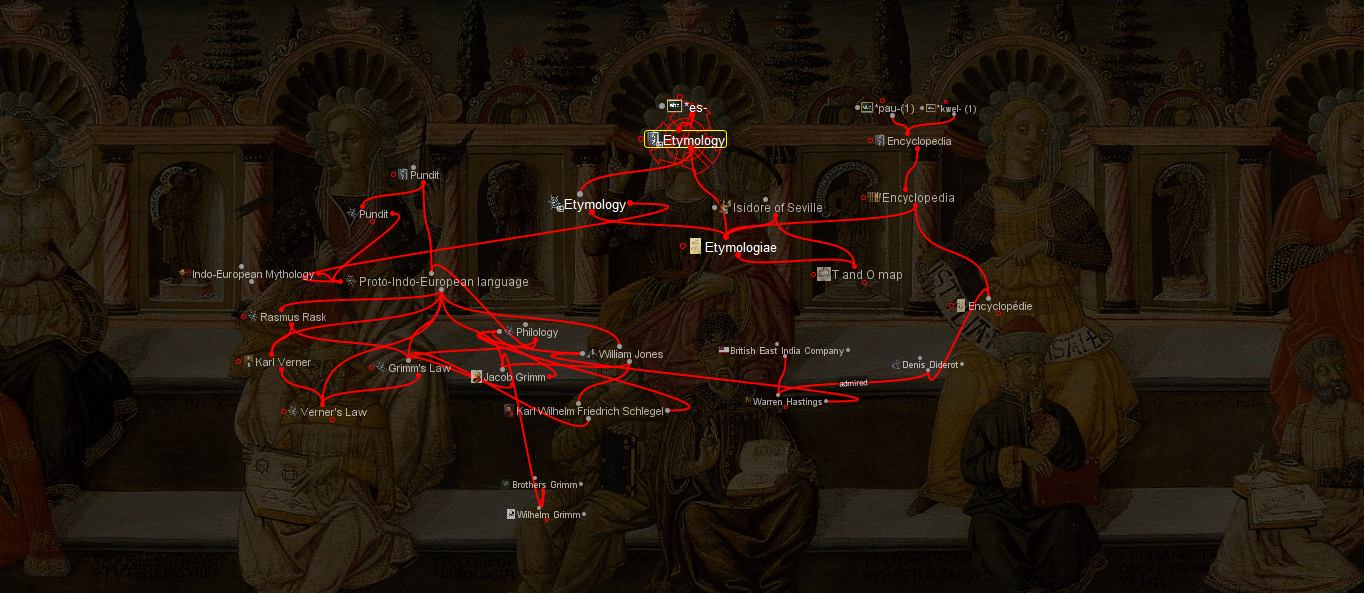

Though they’re not technically stocking treats, one’s Christmas sweet tooth is often satisfied by such confections as fruitcake, pudding, and mince pies. These desserts are all made with dried fruit, the vogue for which in Europe, like gingerbread, seems to have been brought back by those medieval crusaders from the Middle East. Hence sultana raisins from the word sultana, the title of the sultan’s wife and the word currant, a toponym from Corinth. Puddings and mince pies used to be more of a savoury dish than today and indeed mince pies contained minced meat, hence the name, and the puddings were traditionally boiled in a sheep’s stomach, hence the round cannonball shape, before the pudding basin became the preferred method of preparation. The etymology of the word pudding is an interesting one. It either comes from French boudin meaning “sausage”, from Latin botulus which also gives us the word, though hopefully not the disease, botulism. Or it comes from the Proto-Germanic root *pud- and Proto-Indo-European root *bheu- both meaning “to swell”, a root which also gives us the words pudgy (which you might want to remember before reaching for that second helping of pudding) and pout (which you’d better not do because Santa Claus is coming to town). And as yet another song goes, we sometimes refer to Christmas pudding as figgy pudding. The word fig goes back to some pre-Indo-European Mediterranean language, and the Greek form of the word fig has as cognates the tree sycamore (not so surprising), and (believe it or not) the word sycophant, which started out meaning “slanderer”. This comes about from a rude gesture, sticking the thumb between two fingers, which is meant to represent both the interior of a fig and the vagina, and so is called “showing the fig”, which apparently ancient Athenian politicians urged their followers to do to their opponents, while themselves pretending to be above such vulgarity. So feel free to share this factoid with your family over the figgy pudding!

The tradition of putting tokens like lucky coins, thimbles, or beans in the Christmas cake or pudding may go back as far as the Roman winter festival Saturnalia. One of the Roman traditions was the principle of misrule in which master and slave would change places. A survival of this may be the Bean King tradition, in which the lucky finder of the bean hidden in the Christmas cake got to be the Bean King for the day and direct all the festivities. Of course Christmas cakes also contain nuts, and it’s from this that we get the expression fruitcake for someone who is mentally deranged, as a shortening of the expression nutty as a fruitcake, with the word nuts already referring to someone who is “off his nut” so to speak.

To quaff all this down, we often at Christmas parties have hot punch or mulled cider. This tradition goes back to the wassail cup, a drink I mentioned previously in the “Yule” video. The word wassail comes from Old English wes hal meaning “be hale” or “be in good health”. A toast, if you will, which is appropriate because the wassail used to actually contain toast, kind of like putting croutons in soup, along with all kinds of other ingredients that you wouldn’t expect in a hot punch, such as egg, nuts, and cream. And in fact that’s where we get the expression to make or drink a toast, as well as “the toast of the town”. The story goes that a gentleman, back in the 18th century in the town of Bath, upon seeing a beautiful woman bathing in the public baths, as a gallant (if somewhat saucy) gesture, scooped up a drink from the bath water and drank to her health. His witty companion stated that he didn’t care much for the drink but would have the toast, that is, the woman in the water. And apparently from that we get the now well-known expression.

So here’s to your health over the holidays! I’ll leave you, as an extra present in your stocking, since you’ve been so nice, the Christmas videos from the last two years in case you have seen them.